Potatoes:

Potatoes were introduced to Ireland in the sixteenth century and since then have become almost part of our identity. For many years, they were the staple diet of the people and the recurring shadows of the potato famines of the past still hold a strong emotional charge today. Because of the huge part the potato played in our diet as a nation, it is not surprising to find that potatoes were grown on all the farms featured in the project.

Elizabeth Shiels recalls that they grew approximately five acres of potatoes in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The varieties they favoured were Arran Victory, Arran Banner, Kerr’s Pink, DiVernons, Home Guard and Sharpe’s Express. James Armour’s father grew around six acres in the ‘40s and ‘50s (increasing in subsequent years), of mostly Arran Victory and Kerr’s Pink for the market and some Golden Wonders for themselves. Harry Armstrong’s father grew five acres or so of Arran Victory, Arran Banner and Dunbar Standards, while Harry himself concentrated on Arran Consul and grew ten or more acres. Charlie Convery grew up to fifteen acres of potatoes whereas his grandfather grew five. Again, he favoured Arran Banner, Arran Victory and Kerr’s Pink. The amount of ground given over to potatoes on McNamee’s farm varied from five to fifteen acres, depending on whether Raymond’s father took on extra land. In earlier years, Arran Victory were grown but they moved on to Arran Consul for the seed market.

In the early days the type of potato was mostly Arran Victory, they would have been marketed as a table potato. They had to be graded….. the real big ones you kept at home and the small ones. They would have been boiled on a Saturday and fed to the pigs…….In later years we moved on to Consul. They were exported to the Canary Islands and they could probably come back here as early potatoes. The potatoes would have been sold to an agent in the town here, Harry Canning, who bought the potatoes for another agent at Toomebridge by the name of Alex Bell. Alex’s name appeared on all the bags…….. Harry had a fish and chip shop in the town but none of our potatoes were used for Harry’s chips. …….Prices would have fluctuated a right bit some years you would have got about £5 a ton then maybe £10, then on up to £15…….whatever the reason would have been. (Raymond McNamee)

We grew up to about 10 acres when I started farming. At that time it was mostly seed potatoes we grew. Arran Consul was the variety and they were exported to Spain. They would have been planted there at an earlier time of the year because the climate was warmer. The seed suited our ground better as you had to burn down the taps earlier, meaning an earlier harvest. A lot of my ground would have flooded later on so we liked to get them dug earlier. You had to burn the taps earlier to stop growth and keep the potato small so it suited my ground and Arran Consul did well as my ground was fairly heavy. The Consul was a round white potato but very watery and soapy in texture and not good for eating but they were used quite a lot for making chips. That’s where the ware out of the seed went to – some of the local chip shops would have bought them. We would never have used them ourselves for eating. We would have used Arran Victory or Arran Banner for our own use…….About 10 or 15 years ago we decided to stop growing potatoes. The one thing that put me out of potatoes was because the lorry men wouldn’t handle the potatoes unless they were on pallets and then you needed to have a forklift which would have meant spending a lot of money on a machine and pallets…. and we were getting to that age that we felt we would wind down a little bit……. We decided to stop production but my brother and myself worked together at the potatoes. ……..The only difference was in my father’s time the potatoes were always stored in pits in the field over the winter. When I started we had more housing so we could cart them into the yard and store them in a large shed over the winter…….so we brought them in to the store after being dug and then we could start sorting them any time over the winter regardless of the weather. (Harry Armstrong)

Potatoes, were a very labour intensive crop. The ground had first to be ploughed and harrowed to fit in with the crop rotation:

….sometimes the lea ground would have been ploughed up ….you required new ground for potatoes. You weren’t allowed put potatoes in two years following each other…….then (the ground) could have been ploughed for corn- you would have taken a crop off of just corn then back to potatoes. The next year you could have maybe put in corn again and under-sown it with grass-seed. On the fifth year a crop of first cutting hay was saved. That was when my father went to the dole office and hired men to tie the grass seed. (Raymond McNamee)

Then the potatoes were prepared for sowing. To make them go further they were cut, making sure each section had an ‘eye’.

You were able to use a large potato….basically seeing where the eyes were on the potato and drawing the knife right through it and spreading them out on some sort of surface. Then maybe giving them a dusting of lime to seal the cut that you’d made. (Raymond McNamee)

The seed potatoes for planting would have been selected by size and stored in a shallow clamp. The corner of the meadow field was always used for this……..our second well was to be found here too. I can still see my father working there on a sunny day, wearing his straw hat and sitting in the shade of the hedge cutting the potatoes ready for planting. (James Armour)

Charlie Convery describes the work of sowing the crop:

It was all done by hand …….the drills were opened by horse or by a tractor…you put farmyard manure in the bottom of the drill and then you walked along just with an apron and dropped the potatoes and spaced them out. Later the potato-dropper came in….it would have come in in the early ‘50s. When they (the potatoes) were planted you had to cover the drills……you needed skill……the drills had to be very straight that time. That was very important. Then you saddle-harrowed them to break down the weeds before the potatoes came through. Then you did what they called ‘scouring’….. you grubbed between the drills and you’d run the drill plough through them and ‘run them up’. Then there was ‘moulding’ the potatoes. That was when you grubbed between the drills and you used a hoe to take out the weeds between the potato taps. Then you ran the drill plough through them. …….For the blight bluestone and washing soda mixed was sprayed on the taps ……with a knapsack sprayer. (Charlie Convery)

To decide when the crop was ready to harvest, after the taps died down the farmer would pull a tap to judge the quality of the crop and the possible yield. The harvesting required a great deal of man-power and there was a strong tradition of closing the schools for a few weeks at this time to allow the children to help. The amount paid increased over the years from five to ten shillings a day. Not only did the money mean a great deal to the children, but it helped with family expenses as well:

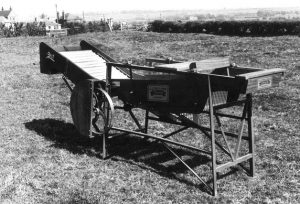

For harvesting we used an old trail digger that was made for behind the horse. Then it was converted into use by the tractor. The potatoes would have been gathered by local ones from the school when they were on holiday. The gatherers were paid five shillings per day. That is the equivalent of twenty-five pence today. (Charlie Convery)

Elizabeth Shiels and James Armour remember the schools closing to allow the children help with harvesting the potatoes:

Then in October, there was the potato-gathering. In my school-days we had two or three weeks off school to help with the harvesting. I remember my Grandmother giving me six shillings for a day’s gathering. I thought I was ‘no goat’s toe’. (Elizabeth Shiels)

We all got prattie-gathering holidays from school…….some years they could be up to three weeks long. When we were finished our own crop we headed off and worked for the neighbours. …….The going rate of pay in the ‘50s was a ten-bob note per day……Some of this went to help to helping my mother with the cost of school clothes or Christmas presents. (James Armour)

Kenneth Murray who lived in the town describes how local children were recruited to play their part in the mid ‘60s: ‘It would have been common at that time for the farmers to cruise about Crawsfordburn on a Friday night booking gatherers for the next day. If we were heading out the country to a farm, getting to and from the field was, on occasion, verging on the comical. I was often amazed at how many gatherers could be transported safely in the back of a mini-van……..One pleasant day still stands out in my mind. I was gathering for Linton in the townland of Grillagh, and we were gathering ‘blues’. The pace was leisurely and the countryside was peaceful. As we gathered the potatoes they were placed in a heap forming a neat line. They were then protected from the weather by soil and straw. This process was known as ‘pitting’……..in the middle of the day the woman of the house brought the food to the field in a large basket. I can remember so well the delicious egg and onion sandwiches we had that day along with the good strong mug of tea. It was almost like having a picnic. I received twelve shillings and sixpence for that day’s work. For a youngster like myself this was as good as it got.’

Note on Potato Types:

The varieties of potatoes grown on the farms in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s (with the exception of Golden Wonders and Kerr’s Pinks), differ from those we are more familiar with today. Different varieties were grown from district to district – depending on local conditions, for example soil type. The potatoes popular in Maghera were:

The varieties of potatoes grown on the farms in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s (with the exception of Golden Wonders and Kerr’s Pinks), differ from those we are more familiar with today. Different varieties were grown from district to district – depending on local conditions, for example soil type. The potatoes popular in Maghera were:

Golden Wonders, a dry, floury potato, date from 1906 and were developed by Mr. Brown from Arbroath, Scotland.

Kerr’s Pink, (main crop) which have a pink tinge with a deeper pink colour around the eyes, were raised by J. Henry in Cornhill. Scotland in 1907. They were launched commercially in 1917 by Mr. Kerr, and arrived in Ireland in the same year.

Arran Victory (a main crop, released in 1918), Arran Consul (released 1925) and Arran Banner (released 1927) were all varieties of potato bred by Donald McKelvie OBE from Aran, Scotland. These are just three of the many varieties he produced. He received his OBE for his services to agriculture. Arran Banner and Arran Consul have light-colored skin whereas the skin of Arran Victory are a very striking vivid blue/purple colour. Arran Banner was particularly favoured as it is resistant to Wart Disease, which was a serious problem in the early 1900s.

Sharpe’s Express, (early) – a small pear-shaped, floury potatoes – is a famous heritage variety that has been around since 1901. They are named after C. Sharpe, Sleaford, England who bred them.

Home Guard, (early) a potato variety grown mainly in Ireland, were raised by McGill and Smith in Ayr in Scotland. Released in 1942 they were very popular during the war years.

Dunbard Standard, a floury potato, were bred by Charles Spence in Dunbar, Scotland in 1936. These potatoes could grow to a very large size. They were known for having shallow eyes, so were good for chipping.

DiVernon, (second early) Introduced in 1922. This potato has a very distinctive flavor. Looking at the list of potatoes above it is very interesting to see how many originated in Scotland illustrating the close ties between the two countries.

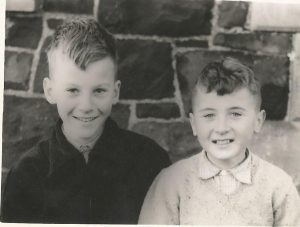

My family moved to Maghera in August 1958, when we were allocated a bungalow in Crawfordsburn Drive. My grandparents were already resident in Crawfordsburn at the time and my association with the town of Maghera and Crawfordsburn began perhaps before I was a year old. By the time we moved ourselves, I was six years old, the youngest in the family.

My family moved to Maghera in August 1958, when we were allocated a bungalow in Crawfordsburn Drive. My grandparents were already resident in Crawfordsburn at the time and my association with the town of Maghera and Crawfordsburn began perhaps before I was a year old. By the time we moved ourselves, I was six years old, the youngest in the family. Conditions varied greatly from farm to farm. I can recall gathering at a farm on the verge of the town on the station road with my good friend Mervyn Cochrane and other children. This was one of the hardest day’s work we ever did. I can remember gathering to meet Mervyn and the large amount of potatoes lying between us. We had to go to the house to be paid, with the two of us receiving ten shillings but with some of the younger children receiving considerably less than this, perhaps as little as five shillings. This caused a bit of a stir when some of the youngsters arrived home, with one or two of the mothers considering going to the house to protest but then, I think, they decided to grudgingly accept it.

Conditions varied greatly from farm to farm. I can recall gathering at a farm on the verge of the town on the station road with my good friend Mervyn Cochrane and other children. This was one of the hardest day’s work we ever did. I can remember gathering to meet Mervyn and the large amount of potatoes lying between us. We had to go to the house to be paid, with the two of us receiving ten shillings but with some of the younger children receiving considerably less than this, perhaps as little as five shillings. This caused a bit of a stir when some of the youngsters arrived home, with one or two of the mothers considering going to the house to protest but then, I think, they decided to grudgingly accept it. he waited until we had gathered it all before digging the next one. This allowed us to have a short break before resuming work. Alternatively, if the farmer was in a more determined mood, he would have been digging the next drill while we were still gathering the previous one, what we would have referred to as ‘digging two ways’. This, of course, meant no break for us between one drill and the next.

he waited until we had gathered it all before digging the next one. This allowed us to have a short break before resuming work. Alternatively, if the farmer was in a more determined mood, he would have been digging the next drill while we were still gathering the previous one, what we would have referred to as ‘digging two ways’. This, of course, meant no break for us between one drill and the next.