Lint/Flax Maghera Roots:

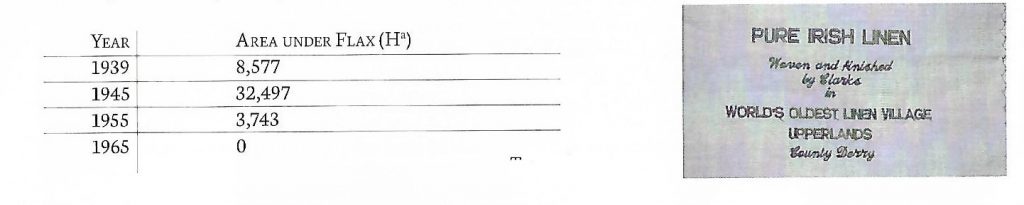

Ulster was the centre of the linen industry in Ireland going right back to the 17th century and throughout this time Irish linen was considered to be of a particularly high quality. However, from the years of highest production in around the 1860s (83,815 Hectares in 1864) the industry went into a steady decline with only temporary recoveries during the First and Second World Wars.2

R McN In the earlier times, there was always flax grown right back to my great-great-grandfather’s time. During the First and Second World Wars, a lot of flax was grown to be made into stretchers for carrying the casualties of the battlefields. I also read somewhere that linen was used for making the wings of small bi-planes.

‘Although Irish flax served as an effective substitute for continental supplies during times of need, the crop was less dependable than the Belgian. It was expensive to produce and subject to variations in terms of price and yield. Quantity became more important than quality. After the war, supplies from abroad were quickly re-established, a consignment of Russian flax arrived in 1945 and members of the Flax Development Committee visited France and Belgium in the same year.’3 The import of cheap supplies combined with the increasing reluctance of farmers to be involved with such a labour-intensive crop meant the writing was on the wall for the growing of flax in Ulster. By 1962 it was no longer even recorded in the annual agricultural statistics for that year.

All five farmers taking part in the project remember flax or lint being grown on their farm, and all testify to the hard work that went into its production. Not only was the work labour-intensive but it was also unpleasant. Methods of cultivation had not changed over three-hundred years.3 Although flax-pulling machines were used on the continent, and were manufactured in the 1940s by James Mackie and Sons Ltd in Belfast, they came too late to make any difference to the virtual disappearance of the crop from Northern Ireland.

E S I remember a flax pulling machine being demonstrated on our farm, it was of Belgian manufacture but I think it wasn’t a success. Maybe the human flax pullers didn’t welcome the machine.

C C We grew a little, not much, it was just dying out at the time and that would have been the middle ‘50s I think. Here there may have been some grown a little later than that….. I was glad to see it go, it was very hard dirty work.

H A When I took over the farm I never actually grew any lint……I think farmers stopped growing it because cheaper supplies were being imported from Russia. I remember seeing a poem somewhere about Russian Flax. They started using a system where they hadn’t to put it into the dams, a chemical was used so that the lint didn’t have to go into the dams. It never really got going here……lint disappeared completely in the late ‘50s.

The flax had to be pulled by hand, as the valuable fibres run the length of the stalk right down to the root. Also, cutting allowed the sap drain from the plant and damaged the fibres. Machines, even today, do not pull the flax up from the root so the finest linen is still made from hand-harvested flax. Harvesting the lint was a backbreaking task and usually neighbours came to help with it – Four handfuls made up a beet or sheaf and this was tied with a band made from rushes.

The flax had to be pulled by hand, as the valuable fibres run the length of the stalk right down to the root. Also, cutting allowed the sap drain from the plant and damaged the fibres. Machines, even today, do not pull the flax up from the root so the finest linen is still made from hand-harvested flax. Harvesting the lint was a backbreaking task and usually neighbours came to help with it – Four handfuls made up a beet or sheaf and this was tied with a band made from rushes.

R McN I remember it (the lint) growing in that field where St Pat’s is now – it’s about five acres. The lint all had to be pulled by hand but before the pulling started there had to be rushes cut to make bands to tie it into sheaves or beets. I had to make the bands by tying two lengths of rushes together. That was called ‘rush band knotting’. You pulled the lint against the knee at an angle and laid it on the rush band. When it was near the right diameter the band was tied in a knot and then you had the beet.

E S I have clear memories of the flax pulling, we called it lint pulling. There were teams who carried out this task, as it was a skilled craft. The flax was pulled from the ground by the root and literally wrapped around the legs of the worker and then stacked in stooks it was an art in itself.

E S I have clear memories of the flax pulling, we called it lint pulling. There were teams who carried out this task, as it was a skilled craft. The flax was pulled from the ground by the root and literally wrapped around the legs of the worker and then stacked in stooks it was an art in itself.

J A The lint crop was ripe for pulling in August or early September when the purple flowers on the stalks had faded and fallen off. Lint stalks were pulled by hand and the job could take four or five men. Again the morrowing system was vital, with neighbours coming together to help. Lint was pulled, not cut, and there was a certain knack to it. First, your two hands grasped a bundle of stalks. Then you pulled down at an angle and finished with a twist of the wrist to get the bundle out cleanly. This bundle was placed on a band made up of rushes. When the bundle of stalks was considered large enough it was tied with the band to form a beet.

The most troublesome part of the business came next. This was known as ‘retting ‘ the flax. This was generally done in a specially constructed dam on the farm. Usually, the dams were dug near a river and were long and narrow in shape. The point was to separate the ‘shous’ or centre parts of the flax from the surrounding fibres. Most farmers in Ireland retted the flax soon after pulling. The lint retted best in stagnant water as the bacteria could build up there and speed up the process. If they remained in water too long, the fibres deteriorated.

To turn the dried lint into thread for weaving is the first step is ‘rippling’ where the stalks

are pulled through a coarse comb to take off the ‘bolls’, or seed pods. Courtesy Fred Faulkener

R McN The beets were then transferred by a tractor and trailer to the lint dam. The dam was full of water to a depth of about three feet. The beets were put into the dam with the heads pointing downwards and the roots sticking up. The roots did not have to be under water. When the dam was full of lint we had to gather stones and place them on top of the beets, this was to ensure they did not rise out of the water. This process was called ‘retting’ the lint. As a young boy I had to go down to the dams every day to ‘tramp the lint’. You had to walk over it to make sure it was all under water. The lint would stay in the dam for about ten days but when it was coming near the time my father would pull out one of the straws. He would then start rolling and breaking it to see how the fibres were behaving. When it was ready, the stones had to be manually removed and then the dirty work started. Someone had to change into old clothes and shoes, lower themselves into the smelly stagnant water and physically throw the beets out on to the bank of the dam. This was a very heavy dirty job because the sheaves were double the weight of when they went into the dam.

E S During the lifting of the lint from the lint dams, if you had gone out at night the smell throughout the country would have knocked you down. We ladies, if we went to a dance around this time, and we knew our partner had stood waist deep in a lint dam that day throwing out lint, we steered clear of him. Even after a good bath hours earlier, the smell permeated the dance floor when the heat got up.

J A The lint was left in the dam for up to three weeks to rot. This process was known as ‘retting’. During this time the water in the dam became toxic poisoning any form of life that lived in it., including the eels which would leave the water and come out on the dam banks to die….. I remember collecting the dead eels with my brothers and using their long slender bodies to make designs on the grass. …After retting the sheaves had to be removed… this usually fell to my cousin Robert to do…. The water he had to stand in stank, was dark brown in colour and had a dense slimy texture. Definitely not a job for the faint-hearted.

The lint was then spread out to dry, usually on a south-facing field.

The stalks are made up of two layers that must be separated. First, they are broken in a ‘breaker’ or ‘lint brake’ to make it easier

to take off the rough, woody part and then the remainder of the

unwanted material is scraped away with a wooden ‘scutching knife’.

Courtesy Fred Faulkener

C C ….it had to be spread out and allowed to dry. When it was dry enough it had to be tied up again into beets and then it had to be ‘gaited’ which meant two beets propped each other up and this continued in a row for about three yards.

E S It was imperative that the weather didn’t become stormy when the lint was drying. The flax was light and under windy conditions the crop was blown against hedges and this could badly damage the recoverable linen. That told a bad tale when the crop went to market to be graded – I remember farmers coming home from the flax market and relating to the family how many stones 2AVP (avoirdupois) their crop had yielded to the peck. Flax was very flammable – I remember a fire in the barn at Tirnony. It was caused by a spark from the tractor exhaust.

When it was considered that the process was complete the flax was brought to the local mill for scutching. Mills were very common then and there were several around Maghera.

C C It went to the local mills, Higgins was one of the local mills. McKays also had two scutch mills and they were all in the area.

E S The mill to which we took the flax was owned by my mother’s brother Bob Cunningham of Grillagh. This was my mother’s homeplace. Bob’s grandfather, my great-grandfather, Robert, with the assistance of his wife the former Margaret Moore (who came from a mill family in nearby Macknagh) founded the mill.

R McN The flax mill belonged to my grandfather. When it arrived there it was stored with other people’s flax but my grandfather had it all marked so he knew who it belonged to. When your time came you had to go down to the mill and give a hand with the scutching process.………After scutching he would have taken it to a market in Magherafelt where he would have looked after the sale and try to get as good a price as possible.

This is the final step in dressing the flax. The fibres are split and straightened by being drawn through a graded series of combs or ‘hackles’ The long fibres are used for weaving and the shorter coarser fibres which catch on

the comb (called ‘tow’) can be used to make rougher cloth.

The woody waste matter, known locally as ‘shous’ was often used as firewood. Courtesy Fred Faulkener

As Raymond McNamee explained, after the scutching process, the stalks would have been taken to the market in Magherafelt and this is where the buyers from the linen mills, for example Clark’s of Upperlands, would have come to select the best lint. This process was overseen by the owner of the scutching mill.

The first step in turning the dried lint into thread for weaving is rippling: Here the stalks are pulled through a coarse comb to separate the ‘bolls’, or seed pods. The next step is ‘scutching’. The stalks are made up of two layers that must be separated. First, they are broken in a ‘breaker’ to make it easier to take off the rough, woody part which falls away leaving the flax fiber behind. They can be cleaned further at this stage using a flat wooden scutching knife. ‘Hackling’ is the final step in dressing the flax. Here the fibres are split and straightened by being drawn through a graded series of combs. The long fibres are used for weaving and the shorter coarser fibres which catch on the comb (called ‘tow’) can be used to make rougher cloth. The woody waste matter, known locally as ‘shous’ were often used as firewood.

In earlier years this process would have been carried out as a cottage industry.

2(The Irish Flax Famine and the Second World War. Jonathan Hamill page 248 Industry Trade and People in Ireland 1650-1850 essays in honour of W.H. Crawford Edited by Brenda Collins, Phillip Ollerenshaw and Trevor Parkhill Ulster Historical Foundation 2005).

3(Bell page 177).